How to Identify Mushrooms and Where to Find ThemBy Linnea Gillman and Jason Salzman When folks who hate mushrooms see one in the forest, they can simply hike in the other direction. But when people who hate mushrooms see one growing in their lawns, a deep anger emerges that, in many cases, only subsides when they kick or chemically exterminate the peaceful mushrooms from the grass. It’s time to look at a mushroom in the grass not as a threat but as an opportunity. Lawns and gardens offer you a place to overcome your fear of fungus. The first step to shedding mycophobia is to learn how to identify mushrooms. Once you get going, you’ll soon be identifying mushrooms just like you can identify broccoli in the supermarket or your uncle in New York. Mushrooms emerging from the lawn will look like old friends. It just takes a little time and patience. The best way to start is to set a goal of learning to identify a half dozen mushrooms in your first season. This avoids the problem of being overwhelmed and discouraged by all the weird mushroom characteristics and impossible-to-pronounce-and-remember Latin names. Start slow and add to your knowledge base each year. How to Find MushroomsYour first bold move toward identifying mushrooms is to find them. Equip yourself with a pocket knife, a sack or backpack, and a roll of wax paper for wrapping specimens. Walk, ride your bike (our preferred method), or--if you must--drive your car around the neighborhood and see what you find. In urban areas, mushrooms can literally grow anywhere, from your basement to the empty lot next door. Look in grass, under bushes, along streams, on wood, in flower pots. There’s no secret to it. Over time, however, you will learn which habitats your favorite mushrooms like and when they might grow, and you will look there first. Here’s the gist of how to do it: We know that oyster mushrooms like to grow in the spring (if it’s been wet) on cottonwood stumps in my back yard. That’s where we look first. Next, we check any stump we can find, particularly stumps from the kinds of trees that we know oysters like to grow on. Most city mushrooms grow in lawns or flower beds with or without manure or wood chip mulch and on live trees or wood stumps. But other sites are also productive -- empty lots, under trees, and indoors in flower pots. Unkempt lawns, infrequently mowed, with weeds (spared from herbicides) are the most productive. Some common urban species tend to grow in or near disturbed areas. For example, look for the urban mushroom (Agaricus bitorquis) in hard-packed soil; the shaggy mane (Coprinus comatus) along roadside; and puffballs near curbs. Other preferences appear more specific -- stinkhorns (Phallus impudicus) under lilac; shaggy parasol under spruce trees; and Japanese parasol (Parasola plicatilis) under hawthorn trees. Keep an eye out for the domicile cup fungus (Peziza domiciliana) growing in the basement on moist walls and carpets. Combine your knowledge of where mushrooms like to grow with your insight on when they like to grow there. For example, most mushrooms grow in Denver in April through September. The winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) appears earlier and survives later. The mica cap (Coprinus micaceous) is also most common in spring and fall. You’re more likely to find the shaggy parasol (Lepiota rachodes) and the inky cap (Coprinus atramentaria) in the fall. The fairy ring mushroom is around all summer long. Moisture, of course, is also key. Irrigation by the city and property owners stabilizes ground moisture, supporting mushroom growth even in dry periods. However, a soaking rain will trigger the most intense fruitings. Look in the north- and east-facing lawns and gardens after a rain. These areas, in the shadows of houses in the hottest times of the day stay wetter longer than the west and south-facing sides. Puffballs (e.g., Lycoperdon species) and their relatives are most resistant to drought. The fairy ring mushroom will dry out and then reconstitute following a rain. How to Pick MushroomsOnce you’ve found mushrooms, you need to determine whether they are growing on private or public property. If it’s private, ask permission from the property owner to pick them. Most of time, you’ll be encouraged to remove as many as possible. (See discussion in Introduction.) Pick mushrooms carefully in order to preserve the characteristics that you will need to identify the fungus later.

How to Identify MushroomsWhen you’re finished with your mushroom hunt, gather together and unwrap the mushrooms that you’ve found. It’s best to have an experienced collector on hand to help you identify them. But a careful beginner with a couple mushroom field guides can begin to identify mushrooms. Examine your collections one at a time. There is no single rule that allows you to determine if a mushroom is edible. Similarly, it would be wrong to say that all white mushrooms are edible. Or all brown ones or all red ones. The only way to identify a wild mushroom is to know the characteristics of the mushroom that you are identifying. The best way to avoid making mistakes is to know not only the mushroom you want, but also mushrooms that look like your desired mushrooms. If you know your “lookalikes,” you are less likely to misidentify mushrooms as a result of your failure to note a couple key characteristics. Smell it.Flowers aren’t the only things that smell in the garden. Mushrooms have amazing smells, which can help with identification. The corn silk smell of some Inocybe species takes some people back to their childhoods of eating fresh corn every day, all summer long. Don’t miss one of the very distinct characteristics of a mushroom and find out where it can transport you. Here are a few mushrooms that you can sniff from lawns and gardens.

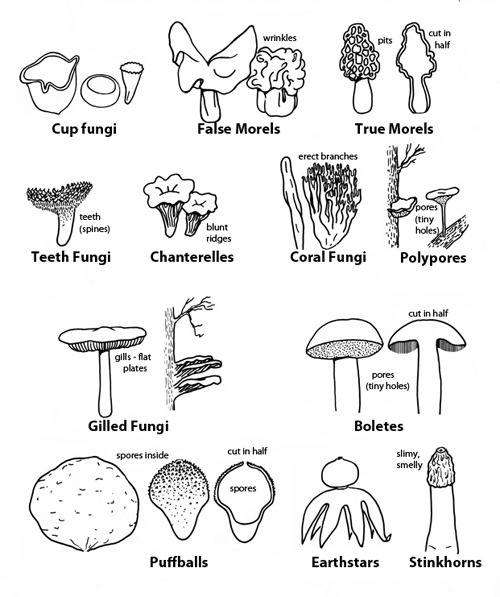

Touch it.Not all mushrooms are the same to touch. They are fuzzy, slimy, dry, smooth, spiny, hairy, scaly, waxy and more. It’s important to note how the mushroom feels. Taste it.Once you’ve learned a bit about mushrooms, you can begin tasting them to help you identify them. For example, Russula emetica is intensely bitter. Take a small piece on the tip of your tongue, hold it there for a few seconds, and then spit it out. If you spit it out, it won’t hurt you. Make a Spore PrintMushroom spores come in all colors from white and black to pink and purple. Determining the color of a mushroom’s spores can help you identify the fungus. Even though spores are microscopic, you can frequently figure out their color by making a “spore print.” Most city mushrooms produce spores on gills, which are the blade-like structures on the underside of a mushroom’s cap. To make a spore print, place the mature mushroom, gills facing down, on a white piece of paper. Cover it and leave it for a couple hours, and you may find a beautiful--and delicate--spore print. Mushrooms that don’t have gills produce spores in other structures. A puffball, which starts as a solid white mass, slowly dries out, finally puffing out dust-like spores when it is squeezed or disturbed. Some mushrooms produce spores in “pores,” which appear under the cap instead of gills. Other mushrooms make spores on “teeth,” spine-like structures under the cap.

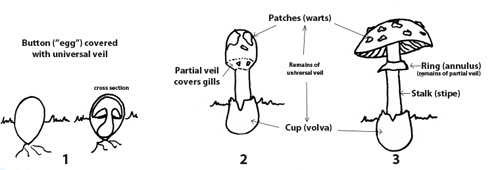

Look for a Cup, a Ring or WartsIn addition to producing spores of different colors, mushrooms grow other structures that provide clues to their identities. For example, the diagram below illustrates the development of mushrooms in the genus Amanita. It starts (in figure below) as an “egg” or “button,” covered with a “universal veil.” When it emerges from the button (in figure two), the remains of the universal veil leave the “cup” or “volva” at the base and the “patches” or “warts” on the top of the cap. At this stage, a “partial veil” connects the cap to the stem, covering the gills. When the cap expands from the stem (in figure 3), the gills become visible, and the remains of the partial veil form a “ring” on the stem. If a mushroom that you’ve found has these structures--and other information is consistent--you may conclude that you’ve found an Amanita. But you must be thorough because other gilled and non-gilled mushrooms may have these structures, such as a ring or cup, as well.

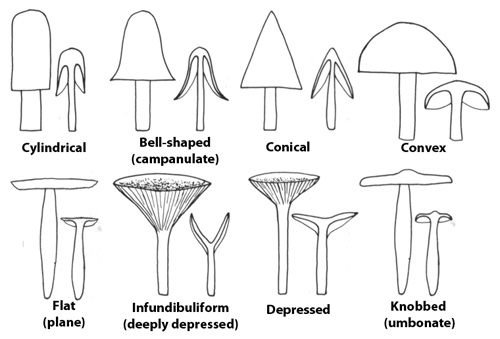

Look at the Shape of the CapMushroom caps come in many different shapes. You should look carefully at the mushroom’s cap during various stages of development. Some young mushroom caps may be conic of convex, later becoming plane or depressed. Also be on the lookout for slight variations in cap shape, such as a “knob” or “umbo” on top.

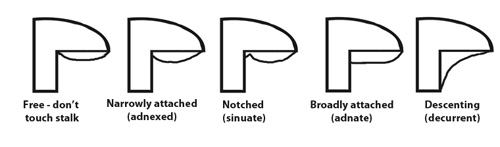

Look at How the Gills Attach to the CapA mushroom’s gills--if it has gills--attach to the stem in several ways. Some gills are not attached to the stem at all. These are called “free” gills. Others are decurrent, running down the stem. It can sometimes be difficult to determine exactly how the gills attach to the stem without looking at specimens of varying ages.

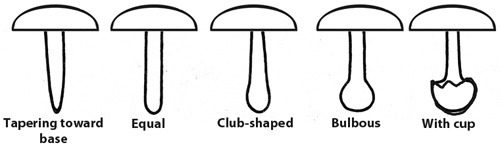

Look at the Shape of the StemMushroom stems are shaped in distinctive ways, from “bulbous to “equal.” Again, it’s best to look at a number of specimens

Look at How the Stem Emerges from the CapThe stem of a mushroom attaches to the cap in a variety of ways. In some cases, of course, there is no stem at all--or no cap for that matter. In other cases, the stem comes from the center of the cap. Look at the Colors and MarkingsWhen you start to look at individual mushrooms in more detail, the amount of amazing stuff to see expands exponentially. And all of it can provide clues to the mushroom’s identity. For example, mushrooms can vary in color from all shades of brown to all shades of red. They can disintegrate into an inky mess. They can have striated or smooth caps. They can have scaly, dotted, or hairy stems. Even the ring on the stem can have distinctive--and beautiful--forms. The best mushroom identifiers hone their skills of observation, allowing them not only to classify mushrooms more accurately but to more deeply admire these unbelievable organisms. Look Through a MicroscopeThis website aims to help you identify mushrooms in the field, under the swing set if necessary. In fact, many mushrooms can be identified adequately wherever you find them with the help of this field guide (and perhaps a couple other for cross-checking), particularly if specimens of varying maturities are available. However, it is impossible to identify many mushrooms with certainty without checking microscopic characteristics. So, if you get serious about trying to put a complete name on all mushrooms you find, you’ll have to learn how to handle a microscope. If you do, you’ll find a new world of spore shapes (spiked, ribbed, lumpy, spherical, elliptical), reactions, and colors to observe. You’ll also have to buy another mushroom field guide because this one does not cover microscopic characters How to Name MushroomsMost mushrooms have both a “common name” (e.g., chanterelle) and a Latin “scientific name” (e.g., Cantharellus cibarius). Unlike most amateur bird watchers or butterfly hunters, who converse about birds and butterflies using common names like Robin or Tiger Swallowtail, most amateur mushroom hunters refer to scientific names when talking about mushrooms. This creates headaches for beginners, because they are forced not only to remember what a mushroom looks like but also how to pronounce its obscure name. Don’t give up on scientific names, even if it seems that—at first—learning them is an exercise in futility. The best way to learn about mushrooms is to seek out fellow mushroom hunters from your local mushroom club and discuss mushrooms with them. And if you are going to talk to them or other people who know about mushrooms, you need to know the scientific names. (Don’t be afraid. Most mushroom hunters are nice, even though they use scientific names and even if they don’t tell you where their favorite mushroom-collecting spots are located.) Most mushroom guides assemble mushrooms into groups based on their shapes, and there are all kinds of strange and wonderful forms. Most of our city mushrooms are in the group “gilled fungi”, but many of the other groups are represented also.

Mushroom Identity DisordersIf you ignore our advice and use common names for mushrooms, you’ll find that they can differ radically from one field guide to another. For example, one familiar urban mushroom called Chlorophyllum molybdites has been given the common name of “Vomiter.” But another common name is “Green-spored Lepiota.” Vomiter is our name of choice for this mushroom, but some of our mushroom friends have no idea what this means. Conversely, some mushrooms have no common names at all. Scientific names for mushrooms can be confusing for the same reasons, but they are usually less confusing. For example, just as some mushrooms have no common names, some have no scientific names. Though it may seem strange given our age of technological advancements, many mushrooms have yet to be described and classified by scientists. So, believe it or not, you may find a mushroom in your yard that is unknown to science. In addition, scientific names change as more information becomes available. As a result, older field guides may have different scientific names for certain mushrooms than newer ones. For example, Lepiota rachodes in the popular guide books is now Chlorophyllum rhacodes. What is a simple mushroom hunter to do? Again, we recommend learning and using scientific names, keeping in mind that--while name changes occur--they affect a relatively small number of mushrooms. Most important, the amateur needs to remember this: Regardless of what name you use for a mushroom--an old name or a new name, a common name or a scientific name-- make sure you’re positive your mushroom is what you think it is. If mycologists change the name of a mushroom that you’ve been collecting and eating for two years, it’s still the same mushroom after its name has been changed. It’s up to you to know the mushroom. ------ Sometimes all the debate about names can irritate amateurs a bit, but it’s part of an important scientific process unfolding in front of us. The real difficulty comes when you have to decide on a name, which a Jason did years ago. He wrote this letter to his friends: My wife had a baby on February 26 at 5:20 p.m. We were hoping for a human, but it looks to me like we’ve got a mushroom on our hands. I don’t know how, but we’ve created a mushroom. He’s sort of like a tiny Marasmius, with a pin head and a long body. (He was two weeks early, weighing about six lbs.) He’s now starting to enlarge at the base and apex. Since we’ve got a mushroom, we thought we’d give him a mushroom name. But why burden him with a Latin name? All his life people would ask, “How do you spell it?” They’d definitely butcher the pronunciation. And you can be sure that mid-way through his life a professional mycologist would change his Latin name, confusing his friends and prompting his parents to hire their own professional mycologist to refute the name change. And there would be wars in the mushroom journals. So, since we are both opposed to war, we discussed giving him a common name, instead of a Latin name. We figure that, even if we gave him a Latin name, some people would insist on using the common name anyway. They’d call him something like “crying Marasmius.” But then, no doubt, another amateur mycologist would dispute the common name, claiming that his real common name is “pooping crib-dweller.” And there would be more wars in the mushroom journals. All of this potential insanity about his name persuaded us to drop the idea of a total mushroom name and go with “Dylan Button Lund,” retaining the mushroom middle name. In the end, we decided we couldn’t completely deny that he is a mushroom. We figured that with a mushroom middle name (Button), even the most dreadfully anal mycologist wouldn’t fight over it. Who cares about a middle name? And what mushroom has one? And besides, the nurses in the hospital loved it. In fact, they suggested we simply use Baby Button. But these nurses didn’t understand the deep emotional scars that Dylan could have sustained from the mycological world. Commentblog comments powered by Disqus |

|